First published in Fwd: Museums Journal, Issue 3: “Alien,” University of Illinois at Chicago, June 2018

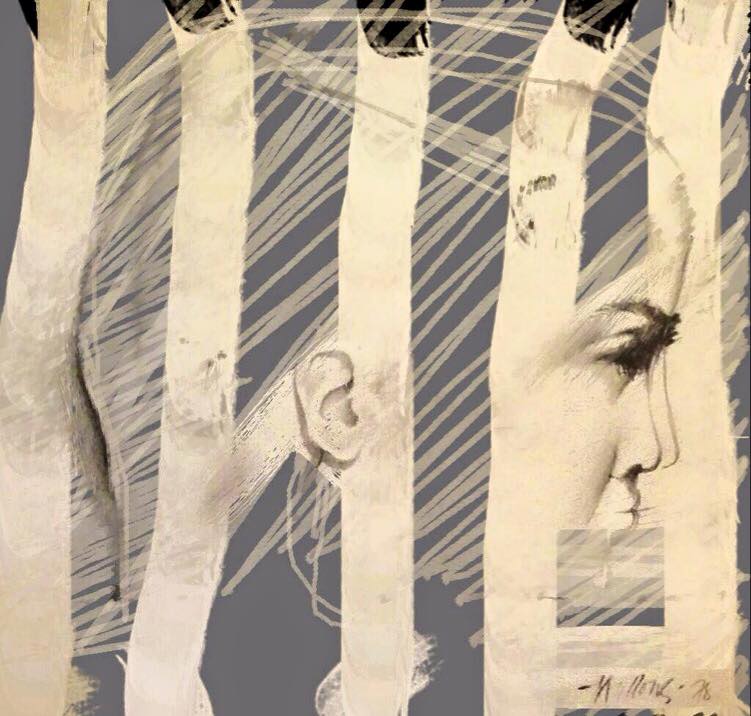

Artist Francesca Mallows (b. 1951) grew up in Johannesburg, South Africa, where her mother was a painter and French teacher, and her father was an architect and founder of the Department of Town and Regional Planning at Wits University. Trained at Wits and at the Académie Populaire d’Arts Plastiques in Paris, she moved to Boston in 1978 and went on to be awarded the 5th Year Traveling Scholarship from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in 1982.

After three decades in Boston, Mallows moved to New Mexico in 2007. She set up a studio in Chimayo, a small town located thirty miles north of Santa Fe and best known as a pilgrimage site for “holy dirt” from the adobe chapel. After New Mexico, Mallows made her way to the town of Delray Beach in south Florida in 2009, where she became involved in local organizing, volunteering her time and assisting her neighborhood alliance with social media. After several years in Florida, she then relocated to Long Island, New York, where she has lived and worked since 2015.

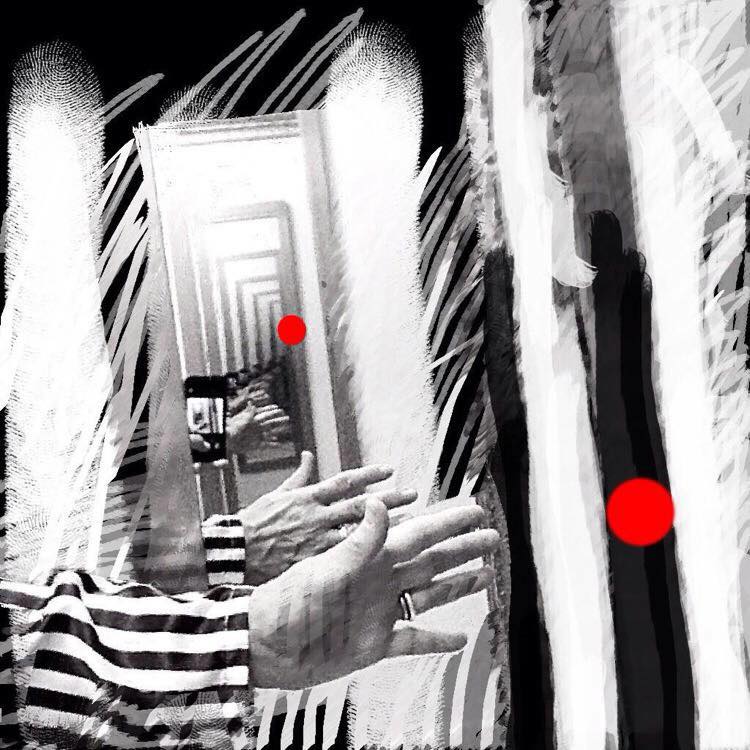

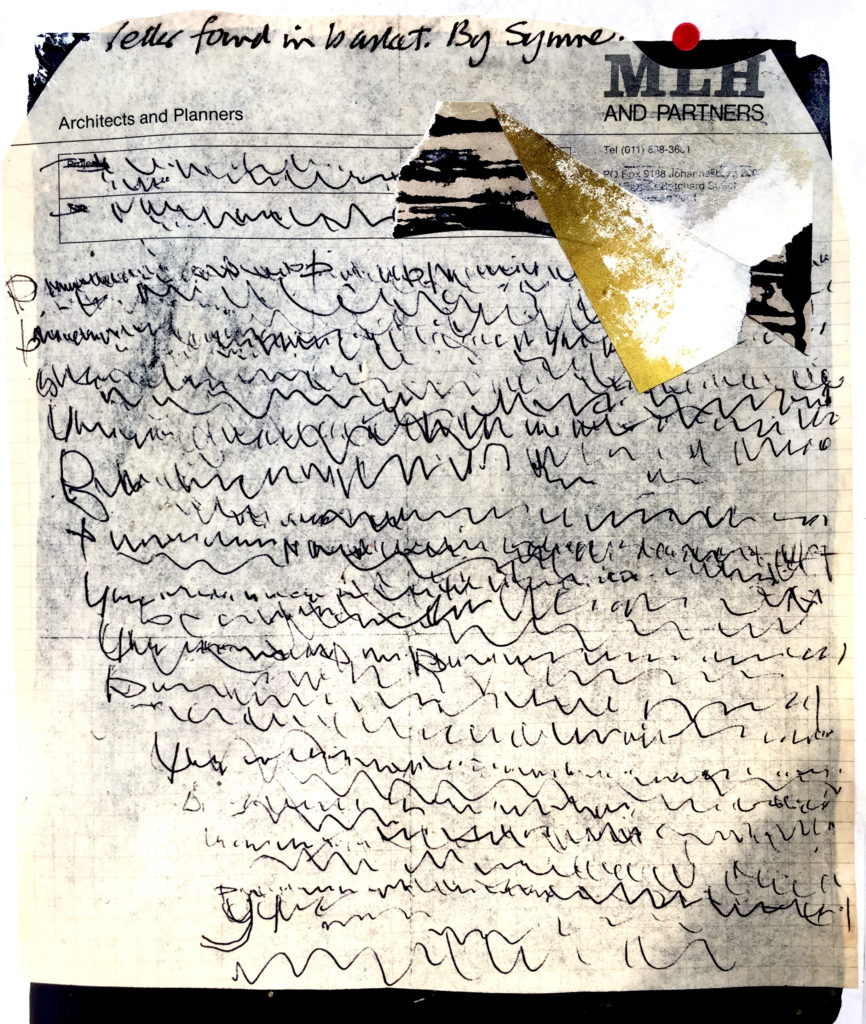

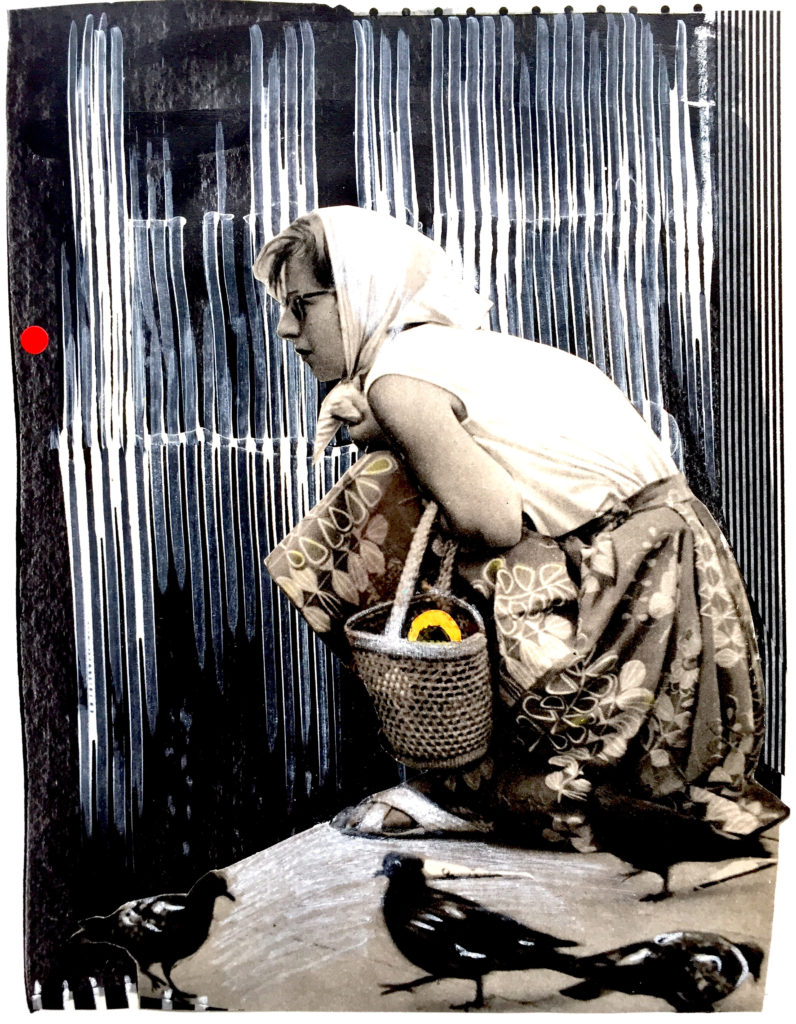

While trained formally as a painter, Mallows often incorporates collage and illustration into her work, which centers around themes of domestic life, family, and immigration. Her newer work is often initially begun by hand, then digitally altered, posted online, and sometimes later reworked in the studio. She maintains active social accounts for herself and her art practice, and one in memoriam of her father.

Joelle Te Paske lives in Brooklyn and is a creative worker focused on social media and communications. She is curious about the opportunities and limitations of digital media for creative practice and cultural change. Using the opportunity of Fwd: Museums Journal as a launch pad, she sat down with Mallows, who is also her mother, to talk about how being a “bona fide alien” has affected her identity, her art practice, and her avid use of social media. What follows is an intergenerational conversation exploring the power of alienhood in art, taste, and belonging.

Joelle Te Paske: Hello. Good morning. This is an interview with [my] mom, about being an alien.

Francesca Mallows: It’s true. I was once a bona fide resident alien. I had a card, a government card that described me as such. And I was proud of it.

If you think about it in science fiction, aliens are the ones with antennae. A lot of the time when I don’t know what to think about something, I say to myself: Think of it as a Martian, as a kind of space-age Margaret Mead, and then things clarify themselves. So I like the whole alien identity, but I don’t think I’m normal in my thinking. Particularly since the [2016] election, it’s taken on a dark and sinister connotation.

JTP: Alien identity you mean?

FM: Yes. But I think it’s being used in different ways.

JTP: I looked it up, the term itself. Alien: belonging to a foreign country or nation; unfamiliar and disturbing or distasteful; relating to or denoting beings supposedly from other worlds. From alienus in Latin, “belonging to another.”

FM: Well, there you go.

JTP: It seems packed into the word there’s the idea of otherness as disturbing or distasteful.

FM: Exactly.

JTP: But you’ve always liked the connotation.

FM: To think like an alien for me is rather exciting because it’s a more creative way of thinking.

JTP: You found it helpful.

FM: With the identity of “alien,” it was relief to sometimes stop thinking and just try to be open, particularly moving around from country to country with different people from different cultures, different belief systems, different racial groups, different genders. You realize that being human is really so much more important in terms of the world.

JTP: Okay, but of course we’re not all “just human.” We have labels and biases we have to live with and work through.

FM: But don’t you think “alien” is the antithesis of human on some level?

JTP: In some ways I think we’re all aliens.

FM: Yeah, but alien to whom or what?

JTP: True.

FM: I’m alien to the Sahara Desert because I know I’m not going to have a roof over my head or food on my table there.

JTP: Well, that brings up another question. Do you see being alien and being at home as antagonistic? Or do you see them as happening at the same time?

FM: It’s true that alien implies that you’re not at home, but that can be a misnomer. And increasingly that is going to change. It’s too easy to make it true right now, given the political climate.

JTP: It’s too easy for it to be essentialized.

FM: Yes, exactly.

JTP: Part of what Fwd: Museums is thinking about is museums as sanctuary. There’s something interesting going on with alien identity and home and the idea of sanctuary.

FM: Yes, I like that a lot. I think they’re definitely related.

JTP: They’re also thinking about occupying digital spaces, which I think is interesting because a lot of your creative life is online. It occupies a digital space.

FM: Yes, that really is a home.

JTP: Exactly. You can occupy a digital space that can’t exist in the world and make a sanctuary—a home—that is centered in art and visual culture. Maybe we all do this, to a certain extent.

FM: The real danger in the online stratosphere is the expectation that we’re all becoming “oneness,” because we’re not.

JTP: Yes, it’s a double-edged sword. There’s the availability of these tools, but because there is so much information, we all have our little channel now. I wonder what that does to art?

FM: Well you know it’s not that different. I’m not sure what it does to art, but I think that’s worth thinking about.

JTP: But I think you’re part of it. You share artwork online, you are in community with artists and critics around the world—not to mention you use emojis and gifs as a language that I haven’t seen anyone else do. Can you explain how you use emojis?

FM: I find symbols. Many times, I wish I could flip them so that I could get a symmetry going around an altarpiece, because the the real meaning is in the central emoji. Emojis are a language.

JTP: Like hieroglyphs.

FM: Yes, in a way. Here’s a subtlety I think many immigrants face. The language you use—even if you’re speaking English—you get misunderstood so many times. I speak English, I speak French, I speak Afrikaans, I speak a little Zulu and Italian. But you get misunderstood. With emojis there’s also an opportunity to misconstrue what’s being said, absolutely. But here’s the thing. What is wrong with implying something so that someone’s imagination has to work [a little differently]?

JTP: Well yes, isn’t that art?

FM: Exactly. We all need to get on board with this emoji stuff and get it right. Because it eliminates the whole alien thing.

JTP: You think it eliminates it?

FM: Well it reduces, it doesn’t eliminate. Eliminates is final.

JTP: I think they’re a great example in a larger question about internet culture, digital spaces, and museums as sanctuaries.

You said you think of being online as a home for creativity. Do you think of it as creative labor?

FM: Yes. But labor is not a bad word for me. Women are in labor to give birth.

JTP: [Laughs] Fair point. But that’s life-generating labor. Do you think being on Facebook is like giving birth?

FM: A little bit, yes.

JTP: You really think so?

FM: Yes, it is. You labor at it and you give birth, you [publish] the post. And sometimes I don’t give a damn if someone reads it or not. I hope people are moved by it if there’s an affinity, but if I’m the only one who likes what I posted, then so be it. I’m the alien.

JTP: Are you the alien if they like it?

FM: That’s a good question. I haven’t thought about that.

JTP: Because if they don’t like it, you’re the alien. But if they do like it, are you still the alien? Or are you assimilating?

FM: I’m still passing judgment.

JTP: So alien for you means passing active judgment.

FM: How can it not? I think support systems come in many forms. I find that the most interesting content comes from visual people, people who’ve been trained visually or who are aware of beauty in their daily lives, be it through hardship or illness or for whatever reason—there’s a way of presenting it that is very human. And so that is what one reacts to. For instance, when you see a photograph of the person who’s making the post, one’s reaction is to acknowledge it and say: Oh, that’s you.

JTP: We’re talking selfies. Definitely. I don’t think it’s just about vanity. I think it’s people going: I support you. And perhaps also: I want you to feel less alien.

FM: Right. It’s about a thumbprint, about a signature.

JTP: What about your art practice? Do you think your use of social media is connected?

FM: I wish I knew the answer to that. I know that part of creation is about pleasure in what you do. I’ve tried so many things and the thing I keep coming back to is just the sheer joy of handling paint, putting it on a surface, making it look like something, making colors interplay. The whole digital thing I’ve flirted with definitely. But in the end, there’s no product and sometimes I just want to hold something other than electronics.

JTP: You think there’s no product, or there’s no object?

FM: Isn’t that the same thing?

JTP: I think of an object as something you can tangibly touch.

FM: You can’t touch that [digital] image once you create it. It’s in the stratosphere. It doesn’t even exist.

JTP: It exists. Of course it exists.

FM: Well, it exists in a very ethereal, alien way.

JTP: No, we can’t just use alien for whatever we want.

FM: Why not? I just did.

JTP: [Laughs] I see that. So, what is your routine for going online?

FM: The way I handle it is a very organic process. I go on and spend an hour or two online, sometimes an hour in the morning and an hour in the evening, and it requires a little faith because there’s so much out there. I just go on and methodically go through whatever’s being fed to me.

JTP: But how did those things become fed to you?

FM: Well, that’s the algorithm.

JTP: That’s true, but it’s not entirely passive. Why are you checking in for an hour or two a day?

FM: It helps me feel part of a community. It can be an echo chamber, but I don’t think one needs to be myopic about it.

Really it’s creating a place for me to feel okay to think the things I think. I keep thinking about this. It’s no different than living in apartheid South Africa in terms of how do you survive this horror story? In that way, it’s become important for sanctuary.

Museums are different than being online, of course. They can just be themselves. You can look at stuff and be moved, and dismiss the stuff that doesn’t move you. That’s the beauty of a museum. You’re immediately at home; you can take in what you want. And no one’s going to judge you.

JTP: Wait, what? There’s judgment.

FM: There’s no judgment, where’s the judgment? You walk past a painting, and say, “Now that is crap. I don’t know what it’s doing in this museum. It shouldn’t be there.”

JTP: But even feeling comfortable enough to call something crap is exemplary of you having a history and an awareness and a comfort in that space.

FM: Yes. And that plays into being authentic. As Clement Greenberg once said—

JTP: Oh good Lord.

FM: I know. For all the stuff that he did and didn’t do, the one thing he did do which sticks in my head is it’s an act of taste. Once you’ve educated your eye.

JTP: Wait a minute. We’re talking about alien, right? A lot of people walk into a museum and are made to feel alien. They feel like the museum is a place that’s not meant for them.

FM: That bothers me. That really bothers me.

JTP: That’s also why I think digital spaces like social media have potential, despite their pitfalls. They’re intimate, they’re a gateway. You are in a foreign space, but somehow your community can be there too. At its most idealistic. But what are the downfalls of positioning a digital space as a sanctuary?

FM: You’re going to be usurped. The possibility exists that someone’s going to not use it the way that’s it meant to be used. Enormous corporations control so much of it.

JTP: That’s true. The digital tools we have are just that in my book—they’re tools. The way we use them to create alternative spaces or sanctuary spaces are as complex as we are, with all of the bias that that entails.

So, do you think the internet helps?

FM: Oh yes, thank God for the internet. I think we just don’t know how to use it properly yet. We need to be aware of that, and see where it takes us.

This interview took place at Francesca Mallows’ home in Long Island in October 2017. It has been edited for length and clarity. All artwork is courtesy the artist.